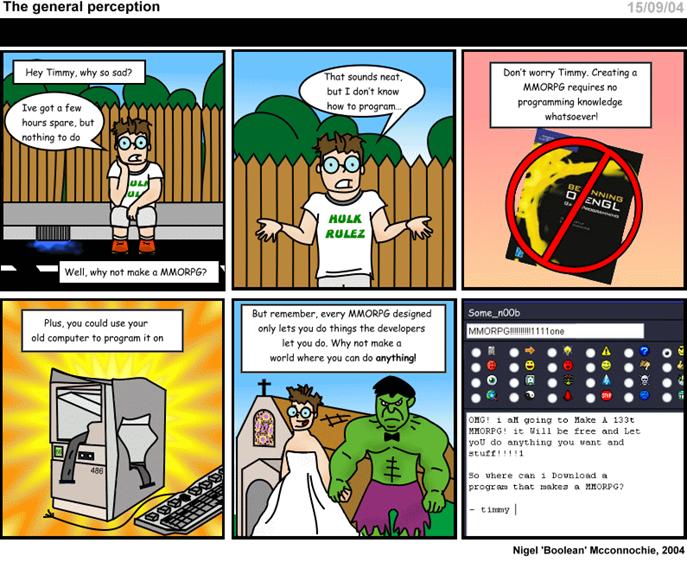

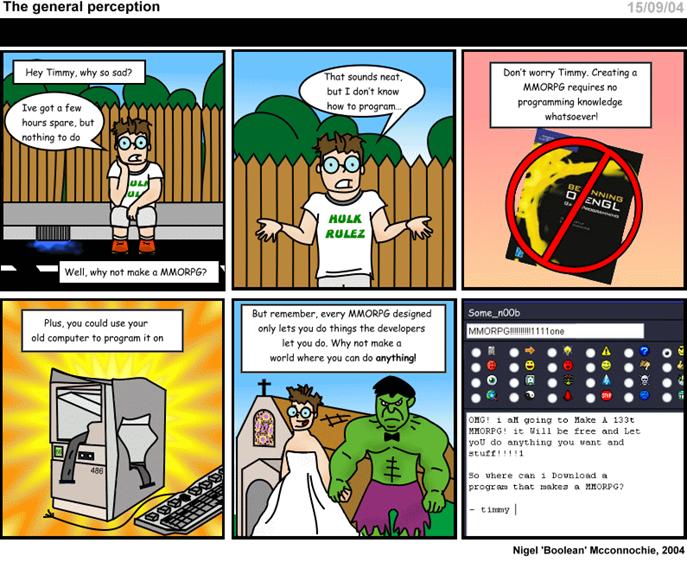

Promotes the idea that in the virtual world you can do anything

A site where you can use real Earth currencies to buy World of Warcraft gold

GameUSD’s site shows price comparisons for World of Warcraft gold from different stores

A player’s account is sold on eBay for nearly a thousand dollars

Items for World of WarCraft are sold on eBay

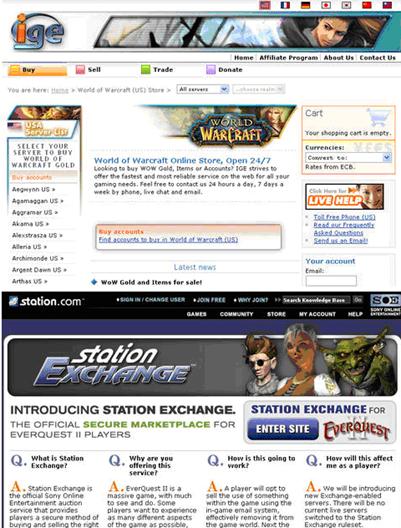

Internet Gaming Entertainment Ltd. and Station Exchange are one of the largest sites for exchanging virtual items

Blurring the line between virtual and real- Players can trade in the virtual world while they are right next to each other in the real world.

World of Warcraft NPCs (non-player characters) have their name and the type of shop they run above their heads

Some players meet outside of the game and form relationships in the “real” world. Here, players create their own real live scenarios based on WarCraft.

|

|

Virtual World Commodities.

by Mercy Sanchez, Kiyomi Shiraiwa, Brian Tan, Alexandra Nguyen, and Christine Dang-Hoang

The creation of the internet has brought along many new developments in our patterns of interaction. According to Keith Hart, the communications revolution of 1990 has transformed our world into a single interactive network. Multi national communities can now set up electronic payment systems and even barter online. “Now that the internet is no longer primarily a research tool, it is becoming increasingly an electronic marketplace” (Hart, Ch 4, 2001). People from all over the world can exchange money and products without ever meeting each other. The internet has become the main medium of communication and exchange for this modern society.

This growth of electronic communication has spurred the creation of virtual worlds in the form of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) such as World of Warcraft (WOW), Everquest, Project Entropia, etc. It is basically an internet based game that can be accessed by a large number of players at the same time. These gaming corporations are rapidly becoming an important industry all over the world. DFC, a game-industry research company, has just released a report that the subscription revenue for online games in 2005 was two billion US dollars. Together, China, South Korea and Taiwan generate fifty percent of the total revenue. However, it is predicted that the United States and Canada will soon surpass them.

Our group chose to focus on the game of WOW because it appears to be one of the most popular games for our age group. It has remained among the top three games on NPD Group's weekly PC-bestseller list since its launch in November 2004. As of February of 2006, WOW is one of the most popular MMORGs in the world. WOW has already been released in French and German and Blizzard, the game’s creator, is currently working on a Spanish version. There are currently six million subscribers.

The game itself is based in medieval times in a world very similar to Lord of the Rings. In the game, there are elves, orcs, humans, dwarves, etc. The player can choose their character’s race, class, profession, and attributes. The object of the game is to level the character up to level sixty. After the character reaches the level sixty, only another character of the same level can defeat him/her. The character can level up through the defeat of various monsters. Their quest is aided by the acquisition of spells, abilities, weapons, and armor; all of which can be attained through the buying or trading of items. These items can be either traded for another item or bought with gold, WOW’s currency. Gold is also earned through the defeat of monsters. The value of these items is determined by supply and demand, much like the economy of the United States.

The phenomenon that we will be studying in our research will be the controversial exchange of WOW items, such as gold, weapons, armor and even characters, for real life US currency. Blizzard restricts the sale of WOW items outside of the network but their regulations do not appear to be effective. The typing in of “buy WOW gold” on google search gives at least twenty million sites. Some of the sites are big corporations while others are small individual sellers in unofficial markets such as EBay. From January to April, two million dollars was spent on WOW gold through EBay exchanges. According to an article in Gamespot, the top seller of WOW gold for the months of January and February earned $44,000 a month.

However, the buying of gold affects more than just the buyer and the seller. In a WOW forum, one respondent posted that “I used to play D2 and it was ruined by the buying of items online.” Exchange of items become more complex with the sale of actual characters. Leveled up characters can cost up to two thousand dollars on EBay. These characters represent a lot more than gold simply because they are the sole product of hundreds or thousands of hours of play. The players that created them have invested their time in creating the character’s personality and type of skill. The players feel that the purchase of these commodities is considered cheating because other players actually spend their time acquiring these items or leveling up their characters by hand. They feel as though their earned items are more valuable because it is intertwined with their own labor rather than someone else’s, an idea consistent with John Locke. At the same time, players feel like they are entitled to sell their commodities because it was a result of their labor. As can be seen, there is an underlying morality in the acquisition of WOW commodities.

According to participant A, a female professor conducting a research study on WOW, the buying of gold is not a really important aspect of the game. People already pay a monthly fee in order to play the game so they would rather spend the time to level up on their own. Castronova states that people that play games pay to have constraints put in. That is what makes the game more interesting. From the same WOW forum, another user posted that powerleveling is “the same thing as a regular person playing for 48 hours straight, but he's just coughing up $100 for someone else to have the fun.” Participant B, a twenty-one year old male, admitted to buying gold online on one occasion but he also stated that it was something that he would never do again. To these players, there is no point in buying any of the items because the exciting part of the game is the acquisition of these items. However, because of the abundance of corporations that sell gold, there must be a large population of players that actually buy it. Unfortunately, our group was unable to find a person actively involved in the gold transaction.

We used the example of WOW to show how complex this intermixing of virtual world commodities and real world currency really is. People can actually make a living from playing computer games. Castranova has estimated that if players are willing to convert all their items to real life currency, players would be making around $3.50 an hour. That is more than the hourly wage in China which would explain why the Chinese government is paying thousands of workers to play these online games and sell their items for real life currency. There is a $100 million market in Asia selling virtual products for computer games. Many people in the United States have reported earning around six figures a year selling items online.

Let us not forget about the flow of money in the opposite direction, the people that are actually paying for these virtual items. One man bought a piece of land within a videogame for $100,000. He took out a mortgage on his house to pay for it.

The philosophical implications of these transactions are tremendous. People are using real life currency in order to purchase an object that is intangible, solely a package of code or a picture on the screen. The objects exist only in an imaginary world and they are not even transferred from one player to another. They are transferred from one player’s fictional character to another. These people are investing money into a world that is contained within a small network of computers. In the real world, the man who bought the land in the game will not be able to consider it as part of his assets. If the item is not real, how is it that it has such high value? Castronova states that economists do not care if the item has real value as long as people are willing to pay for it. “People imbue certain digital objects with meaning; those meanings become shared, making the objects symbolic on a macro level; people begin to manipulate the symbols and meaning just as they do on earth” (Castronova, p 49, ). These objects function as the money tokens of Plato’s philosophy. By paying for these objects in real world currency, the players are legitimizing the value of virtual property. Game currencies, such as WOW gold and EverQuest platinum pieces, only have value because the other players agree that it has value.

Apparently, according to participants B, C, and D, all males, these players recognize that reality and the virtual world are two very different concepts. They are aware of the fact that although people may be paying real money for these items, these items are nothing compared to tangible commodities. These participants verbally acknowledge that real life achievements are much more important than achievements made in the game.

However, according to different sources online, these virtual games are in danger of taking over the lives of its players. In South Korea, a twenty-eight year old male died of exhaustion after having a forty-nine hour gaming session. What could be more important than life and health? These virtual games have little or no outside benefits yet people do not seem to care. In a survey conducted by Castronova in 2001, one-third of adult EveryQuest players spent more time playing games than at their actual jobs. People thought of these games as actual jobs because they could earn real money. Participant C, a twenty year old male, stayed on his computer for hours simply waiting for another character to come and bring him gold. These players have no problems with games consuming their time. Castronova mentioned a man who committed suicide after he suffered severe loss in the game. It is a game and games can restart but life cannot. This man seemed to be lacking a separation between the game and his life. According to Castronova, many respondents to his survey answered that their home was in EverQuest and they merely slept on Earth. The majority of the EverQuest players that he interviewed admitted that they were addicted to the game.

With this new developing addiction to games, there has been the formation of support groups for those that feel neglected by their loved ones. There is one forum on CNET news.com and it is a place where neglected people can post their stories. This mother posted a story about her nineteen year old son and his addiction to WOW. She discovered that he spent four hundred dollars in two weeks buying items for this game. He had also apparently not passed any of his classes during his first year of college and he had turned down a high level position. Another boy, about the age of eighteen, posted about his own addiction to WOW. His grades had also plummeted and so had his social life. He lost two of his girlfriends because of his addiction. There is also another site called gamerwidow.com and many newlyweds posted stories of their new husband’s fascination with the game. Participant C told us about one of his friends that had wasted his income on a game and now he had completely depleted his savings. Many of the stories regarding this addiction are very heart-breaking. Obsession with the virtual world has ruined many relationships between families and friends.

So therefore, after all the horror stories, why do people still continue to be sucked into this virtual world? These players felt that the experiences offered to them within the game were more emotionally enriching than the experiences of real life. They feel that the computers do a better job of socially bonding with them than real people do. In the game the player can make a fantasy version of him/herself as well. Within the game the players can be whoever they want to be. If they ever wanted to be someone that they are not, they can. They can choose their own physical characteristics, such as height and gender, and they can also choose their personality traits, such as intelligence. The players are able to create a second identity. The players also have more of a sense of control within the game. They know what to expect and they know that eventually, if they try hard enough, they can level up. There is a safety net. If the player makes a mistake, the player can start over again with a new character. When compared to the uncertainties of real life, the virtual world does seem appealing.

However, because of the previously stated complications, escaping into the virtual world does not seem like the healthiest path to take. Some people stop because they realize that they need to prioritize and focus on their futures. However, the one reason that might possibly be used to drag a person away from the game is no longer valid with the creation of this unofficial market. Because these people can now live off their earnings from the game, there is no reason to have to leave the virtual world. These people are now justified in playing because it can now serve to support them. Money can legitimize any type of activity regardless of its danger to social relationships. The players now have incentive to play. |

|